Housing's Progressive Paradox

Will Liberals Stop Playing with their Food and Build?

Housing is on everyone's mind these days. Whether you're a renter facing steep increases, a hopeful first-time buyer priced out of the market, or a city planner trying to address homelessness, the effects of our housing shortage can be felt across society. But as I discovered in a recent conversation with The Atlantic’s Yoni Appelbaum on my podcast, Most Podern, there's another troubling dimension to this crisis: Americans are increasingly "stuck" – unable to move to places of opportunity.

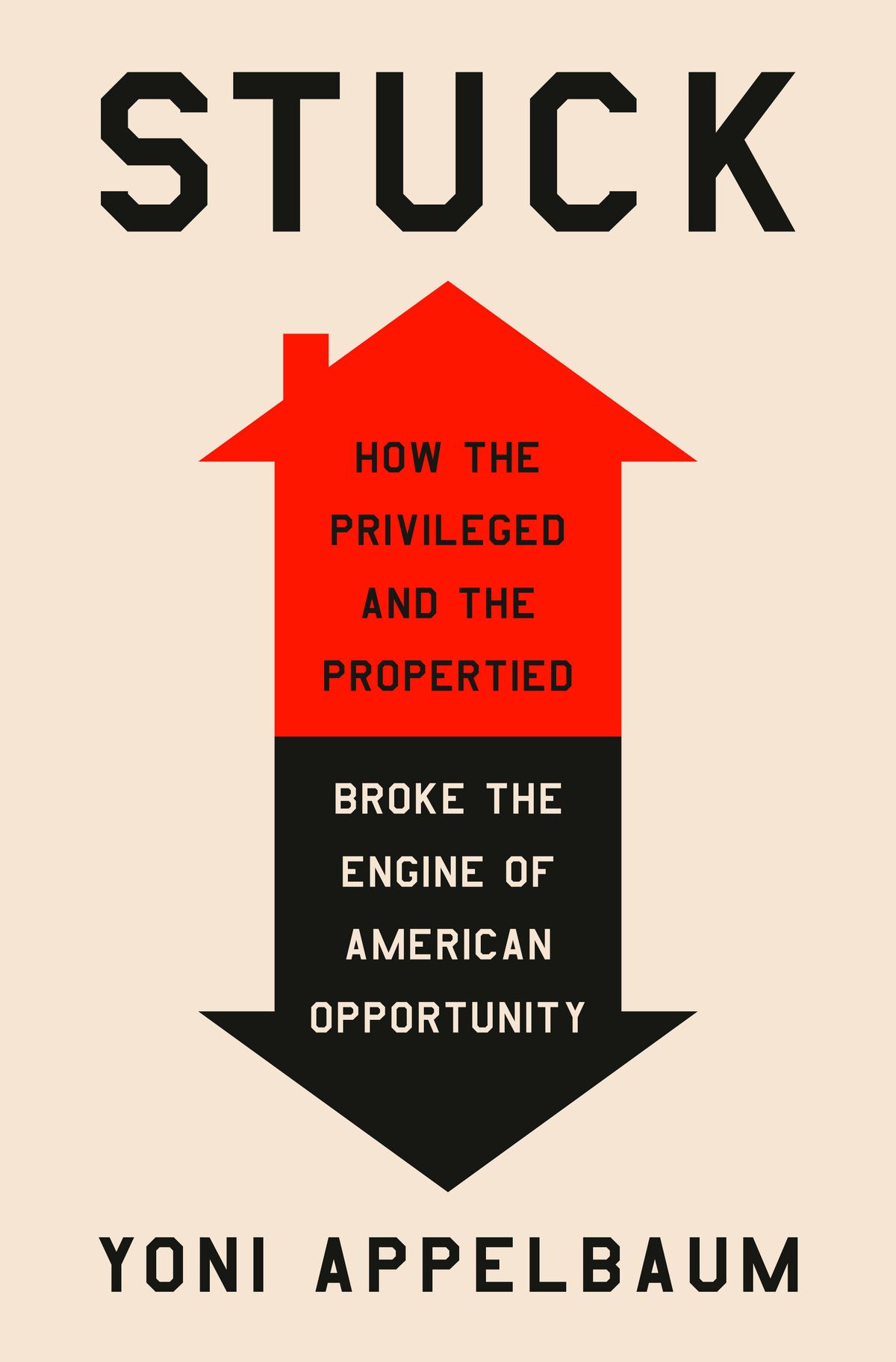

Appelbaum's new book, Stuck: How the Privileged and the Property Broke the Engine of American Opportunity, examines how America shifted from a nation of movement and reinvention to one that has grown increasingly static. I cannot recommend this book enough—it is critically researched and beautifully written. My co-host, Libo Li, has written his own review, and I want to address some of its main points while expanding on the conversation.

Watch our interview with Yoni here:

America’s Mobility Crisis

"For 200 years, Americans moved from the poorer parts of this country toward the richer parts," Appelbaum explained. "That has reversed. Now they move from the richer parts to the places where housing is cheap."

This reversal represents a fundamental shift in American life. Historically, geographic mobility wasn't just about changing locations – it was the mechanism through which people reinvented themselves and climbed the economic ladder. The freedom to move was the freedom to belong, to build new communities, and to pursue opportunity.

"Until 1970, one out of five Americans moved every year," Appelbaum noted. "We just got new numbers from the census. It's down to one out of 13. It's an all-time low."

This decline in mobility has measurable effects. "When people move... they become more optimistic. They are likelier to see that the gains of others lift all boats. The people who wanted to move and then didn’t... grow more cynical, more alienated, more withdrawn." Throughout our conversation, Appelbaum lays out the benefits of moving, from increased societal cohesion, to better aligning economic opportunities to individuals, to regularly rethinking engrained lifestyles. It was refreshing to think about a social practice with seemingly so many beneficial economic, community, and almost spiritual effects. The problem, though, ties to how we treat our built environment, especially around housing.

The Progressive Paradox

One of the most compelling insights from our conversation was what I'd call the "progressive paradox" – a fundamental contradiction at the heart of progressive housing policy. As Appelbaum put it:

"Housing regulations have largely been a progressive project, and so they are most restrictive and most avidly enforced in the most progressive jurisdictions. The tragedy is that those are also the places Americans most want to live because of the other aspects of progressive governance."

This observation struck a chord with my co-host Minkoo Kang, a developer, who remarked that these restrictive attitudes persist in community meetings: "There is a huge ignorance in terms of the scarcity of land and the cost of things." This is not an uncommon frustration with well-meaning developers like Minkoo. Individuals have outside influence on how places are shaped despite not knowing how that shaping takes place. Everyone’s a critic. It’s like the Yelpification of the neighborhood.

This paradox has gnawed at me for years. As an architect in San Francisco and an urban design professor at Harvard, I’ve seen firsthand how two of America’s most progressive cities systematically undermine their stated values through their housing policies. The sentiment has appeared here and there, but more and more people are talking about it in the wake of the 2024 elections.

As a practitioner and an observer, I'm very firm in saying that progressivism has been distracted by proceduralism – an obsession with process over outcomes. Community meetings, environmental reviews, historical assessments, and endless revisions have become how housing is delayed or denied. These meetings claim to provide 'community input,' but in practice, they serve as de facto veto points for housing projects, prioritizing the loudest and most entrenched voices over actual needs. Come to a public meeting on affordable housing and you will know what a vetocracy feels like. On a systems level, progressives prefer one where every concern must be accounted for, every objection addressed, with complete agnosticism toward actual results.

Recalling the NIMBY anthem:

Lift every voice and complain,

'Til the architect and developer disdain,

Making their toil and their work be in vain.

Let our objections rise,

Loud to the city skies,

Not in Our Backyard as our sacred refrain.

The Broader Scope of the Progressive Paradox

Beyond zoning, several progressive policies contribute to America’s mobility crisis. While we discussed many of these on the Pod, there are even more contradictions within progressive housing policy that we didn’t have time to explore. These additional barriers further reinforce the paradox of progressive jurisdictions advocating for inclusion while enacting policies that lead to exclusion.

Rent Control

Rent control is often positioned as a tenant protection measure, but it fundamentally subsidizes demand rather than increasing supply. By capping rent increases, these policies discourage new construction and renovation of existing buildings. Landlords have little incentive to improve properties when returns are artificially limited.

Unlike Phoebe's grandmother's apartment in "Friends" (which became a running joke for its unrealistic affordability), most rent-controlled units aren't passed down through generations. Instead, they create perverse incentives that keep people in housing that may no longer suit their needs simply because they can't afford to move – another form of being "stuck."

Union Labor and Construction Costs

Another progressive value – supporting unions – comes with trade-offs in housing policy. While union labor provides important protections and fair wages for hard-working contractors and subcontractors, it also adds a significant premium to construction costs, often upwards of 30% to total development costs.

More concerning is the active resistance many construction unions have shown toward modular construction – a potential solution for more affordable housing. Modular construction has been stifled in the Bay Area (The Economist) – if it can't find product-market fit in the most technologically advanced and housing-starved region of the country, where can it? Recent YIMBY legislature such as California's SB-4 (the so-called "Yes in God's Back Yard bill), require prevailing wage labor. Given the cost of construction, its uncertain if such policies will actually spur more development.

I also think its valid to note an important reality: the incentives of the construction industry don't align with housing abundance. Scarcity drives up the cost of their services, benefiting their bottom line. This isn't to vilify unions or contractors – businesses naturally pursue profit – but we must acknowledge that these incentives work against goals of creating more affordable housing.

The 30-Year Mortgage

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is an American innovation that provides homeowners with remarkable stability. Unlike many countries where adjustable-rate mortgages are the norm, Americans can lock in their housing costs for decades. It is not a progressive policy, but it has been an important tool of the middle class – a group that progressivism is increasingly losing.

However, this creates another form of being "stuck." When interest rates fluctuate dramatically – as they have in recent years – people who secured low rates become reluctant to move, even when their housing no longer suits their needs. A family that has outgrown their home or needs to relocate for work opportunities might choose to stay put rather than double their monthly payments with a new mortgage.

America should consider making mortgages more portable or transferable, allowing people to carry their favorable rates to new properties, enhancing mobility rather than hindering it.

Class Above All: The Evolving Image of NIMBYism

In progressive discourse, NIMBYism is often framed as a problem of racist and aging homeowners. While Yoni expertly traces zoning's racist origins in our conversation, he also notes how exclusion has evolved. What began as explicitly racial segregation has transformed into economic segregation—a class-based system that achieves similar results through different means.

Today, "Not In My Backyard" really means "Don't Touch My Net Worth." It turns out that the most effective way to convert a progressive into a conservative on housing is to hand them a mortgage. When housing becomes an investment vehicle first and shelter second, people of all backgrounds will fight fiercely to protect their property values.

I witnessed this firsthand while developing a 100-unit affordable housing project in Hollister, California. At CO-, the office I started with my partner Weijia Song, we're handling both development and architectural design, an integrated approach that's uncommon but delivers better, more affordable housing by eliminating the inefficiencies of siloed processes.

When we presented to the planning commission (watch the video here), the opposition wasn't from white boomers but predominantly young people of diverse ethnic backgrounds who had recently bought homes nearby. "We were told this would be a park," one neighbor insisted. "How will our children be safe?" asked another. The catch was this lot was designed for high-density affordable housing over twenty years ago, long before the homes that their owners were looking to protect were even built.

These neighbors, perhaps themselves first-generation homeowners, had bought into the American dream where homeownership equals wealth-building. They were simply protecting their investment using the same exclusionary tools that may have previously deployed against their own communities. Minkoo has been fighting a protracted fight under similar circumstances in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood, to get his client’s project accepted by the local community.

This reveals the most insidious progressive paradox of all: in a system where housing is primarily a wealth-building mechanism, even those who have historically been excluded will, once included, fight to maintain the exclusivity that gives their investment value. The problem isn't demographics – it's that we've structured housing to reward scarcity rather than abundance, exactly as Yoni argues has happened across America's most desirable cities.

The Path Forward

The biggest roadblock to housing abundance is what I call 'construction constipation'—a system where permitting drags on for years while the actual building process takes months. This inefficiency doesn’t just drive up costs and stifle production; it saps energy and momentum from those trying to solve the housing crisis. The longer we allow these bottlenecks to persist, the further we entrench the very scarcity we claim to be fighting.

The good news is that we may finally be turning the page toward policy clarity. One promising solution is 'as of right' construction, as Appelbaum suggests: 'If you publish clear guidelines, and as long as you stay within them, you can just build.' Predictability and accountability go hand in hand in the development process, and ensuring a straightforward path to building would eliminate many of the barriers that have slowed housing production to a crawl.

There are signs of a shift. As I mentioned to Appelbaum, even planning commissioners are now challenging old assumptions: "You shouldn’t be worried about affordable housing making your neighborhood unsafe. You should be worried about whether your kids will have a place to live when they’re 25 or 30." But shifting attitudes alone won’t get us there—we need bold, responsive leadership. And ideally, that leadership should come from a generation that hasn’t yet paid off their mortgage, one that understands firsthand the frustration of being locked out of homeownership and the urgency of housing scarcity.

Getting Unstuck

Addressing America’s housing crisis requires an honest reckoning with its contradictions. Progressive values of inclusion, diversity, and opportunity should align with policies that enable more housing, not less. If we are serious about restoring the engine of American opportunity that Appelbaum describes—the one that once allowed people to move freely in pursuit of better lives—then we must abandon policies that entrench scarcity and exclusion.

We are at a critical juncture. Ezra Klein and Derek Thomas’ new book, Abundance, drops this week, and they’ve been making the rounds on liberal media, pushing its ideas and potential. In a moment when liberal leadership is so clearly MIA—misaligned, ineffectual, and aloof—Klein, with his large following, appears poised to champion a new liberal cause centered on productivity. But as much as I want this to land, I’m not convinced his value proposition will resonate where it matters most.

On one hand, if progressive politics is truly about inclusion, then housing abundance should be non-negotiable—surely, someone will right this ship. Yet, the paradox is undeniable: a system that preserves privilege under the guise of protection. As Stafford Beer observed, “the point of a system is what it does”—not what it claims to do. If our housing policies produce scarcity, exclusion, and stagnation, then those outcomes are the system’s true purpose, whether or not progressives admit it. A reboot won’t happen without realigned incentives.

And yet, the housing crisis exposes liberal contradictions in a way voters can no longer afford to ignore. Over the past decade, I’ve learned one undeniable truth: America can tolerate liars, but it despises hypocrites. The path forward is clear. By confronting this paradox head-on and enacting policies that prioritize housing abundance over ideological purity, we can create cities that are both economically dynamic and truly inclusive. The choice is ours: double down on the contradictions that have stalled mobility or build the future we claim to want. There is no time to waste.

I am just old enough to remember when people could "just build." Before NEPA, before the NFIP, before the ESA.

They did not build charming neo-traditional villages. They built sprawl. They filled wetlands and put mobile homes parks in floodways. They destroyed habitat and prime farmland. They needed to be slowed WAY DOWN. And all we have done in the way of environmental legislation, land conservsation, and zoning since then has barely stopped that in most places.

Whenever you see a change in society, the first variable you should consider is median age, because it’s usually a factor.

In 1970 the median age in the USA was 28. Now it’s nearly 40. Older people just don’t move as much.