Earth Got 266% More Crowded in Just Two Generations

We've Been Living Through The Great Compression - And We’ll Need to Learn to Live Even Closer

There are about 8 billion people on earth. In 1960, there were 3 billion. The implications of population growth for consumption, environmental impact, and urbanization are well discussed. But what's not understood enough is the obvious corollary. In two generations, global society has become nearly three times as dense.

Our entire planet has become dramatically denser, yet most of our policies, practices, and perspectives remain stuck in a less crowded past. The failure to adapt to this new reality is at the heart of our most pressing challenges, from housing affordability to climate change. Embracing population density, the proximity of people to one another, as a core lens could help us better understand and reshape our crowded world.

Planetary Reality Check

When William Anders took humanity's first full family portrait on Christmas Eve in 1968, he captured something profound: an image of encapsulated density. The photo accomplished what no map could, revealing Earth as an integrated system on a single object rather than an abstract realm. It demonstrated what everyone understood but had never actually seen: that we all must share the same planet. Earthrise showed us our blue planet as a whole object, finite, isolated, and complete.

But that family portrait captured a world with nearly 5 billion fewer people than we have today.

Earth hasn't grown physically in any meaningful way. There are about 148.94 million square kilometers of land. But the number of humans sharing it has exploded from 3 billion in 1960 to over 8 billion today. That's an incredible 266% increase in planetary density.

Let that sink in. How many lots, neighborhoods, towns, or cities can you think of that have almost tripled their density in two generations?

A Metric for Living Together

So how should we measure and understand this dramatic increase in planetary density?

The term ecology refers to the relationship between living things (not wetlands and living walls). A critical, if not the most important, relationship in the physical world is the distance between elements.

Looking at our planet through the lens of density reveals powerful insights. Rather than simply counting how many people exist, density forces us to consider how we exist together in shared space. This shift from absolute numbers to relative positioning unlocks a deeper understanding of our societal challenges.

When teaching Urban Design graduate students at Harvard, I'm often given absolute numbers as justification for their projects. But these numbers don't interest me. "Thicken the plot," I tell them, by introducing relative metrics over absolutes. Ratios lead to more questions to answer. They spur creativity, and they reveal relationships, dependencies, and dynamics. Of all the relative numbers, density is the most important for understanding human interaction at any scale.

Take New York City and the state of Arizona, each with roughly 8 million people. But while NYC packs those millions into just 300 square miles, Arizona spreads them across 114,000. That's a huge contrast: about 26,000 people per square mile in the city, compared to just 70 in the state. That single ratio, density, shapes nearly every aspect of life in these places. From transportation and housing to social interactions, resource distribution, and governance, the way people relate to space fundamentally reorders how society functions.

Density allows us to shift our perspective from quantity to quality. The number implies important social and power dynamics when overlaid with contextual considerations like culture, economy, and geography. The human question has never really been about how we live, but how we live together.

While we're busy arguing about whether to allow duplexes in single-family neighborhoods, a question I focus on in my professional life all the time, we should remember that the recent densification of the planet has profound implications.

Focusing on Proximity

Density measured per unit of area is useful for analyzing regions and economies, but it doesn't fully capture what it feels like to live somewhere. It tells you how full a place is, not how close people are.

The comment section of a recent post about my concept of Density Appetite made something clear—many people don't distinguish between density (a measurement) and crowding (an experience). Two New Yorkers, both of whom appear to be on the older side, and one of whom listed their job title as "Full-time Grandpa," began decrying how unbearably crowded areas of the city became and that policymakers were prioritizing increasing foot traffic over the pedestrian experience. The back and forth made me realize that for most people, what matters isn't how many people there might be in a square mile, but how close or how far away they are from someone and by extension how likely they are going to run into someone or have more space to themselves.

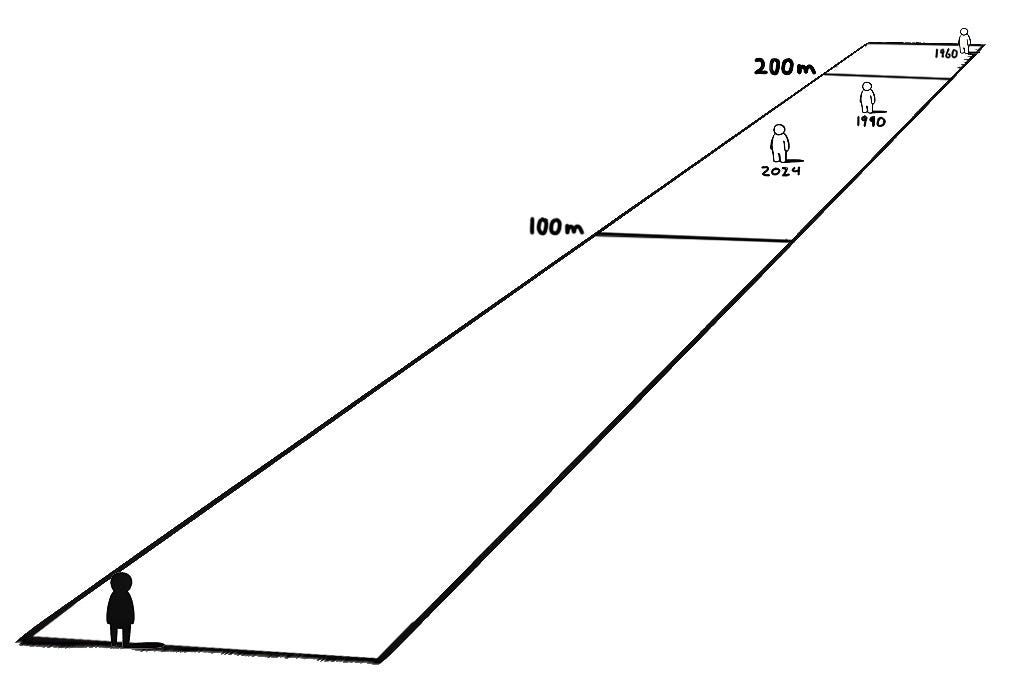

Average Human Proximity (AHP) is the average physical distance between individuals if people were spaced evenly across a given area. It's a simple metric I've come up with, limited by my rusty math capacity, that captures what traditional density measures miss - how close we actually feel to one another.

In 1960, the global AHP was around 222 meters (728 feet). Last year, it it had been reduced to 135 meters (443 feet). On average, every human on Earth is now one football field closer to the next one compared to just two generations ago.

AHP brings density to life in ways traditional metrics can't. It helps us understand why downtown San Francisco feels eerily empty post-pandemic despite unchanged building density. The structures remained, but the people left, dramatically altering the experiential proximity that defines urban vitality.

Let's go back to the city and the desert. New York's AHP is just 9.9 meters (32 feet) across the five boroughs, while Arizona's is 192 meters (630 feet) throughout fifteen counties. It is no wonder that stark differences in human closeness have profound effects on human ecology and, in turn, the forces that structure them, including planning, policy, culture, mobility, and politics.

Average Human Proximity also reveals temporal changes in density. Manhattan's daytime AHP during work hours is just 4.7 meters (15.4 feet), but extends to 10.4 meters (34.1 feet) at night as the commuter tide retreats. This fluctuation of 5.7 meters also demonstrates the dynamic nature of cities, like a heart that pumps population throughout a region. (Source: NYU Wagner Rudin Center, 2012)

I’m not surprised if this idea sounds familiar. During the pandemic, the concept of social distancing - two meters or six feet apart -imposed an artificial lower bound on human proximity. And while the pandemic may now be in the rearview mirror, our thinking about proximity shouldn’t be.

Density across Scales

Density and proximity do not operate uniformly across our world.

Instead, density can be understood across interconnected scales, from continent to dwelling unit, each with its own distinct characteristics, yet collectively forming a network of nested dependencies and ecological relationships. Neither area-based nor proximity-based density averages fully capture the local variation and uneven distribution of human presence.

We intuitively understand that people cluster more tightly in economic capitals than in regional hubs, in cities more than suburbs, and in subway cars more than parking lots. While direct comparisons between different units of area, such as square kilometers and square meters, can be difficult to grasp (like guessing how many beans are in a jar), it is possible to draw meaningful connections between these nested scales. AHP allows us to compare across scales using a single linear metric that aligns with human perception and proportion.

Global (geopolitical fuel): Density drives resource competition, migration pressures, and transnational challenges. Corollaries – GDP, immigration, workforce and market size

National (varied densities): Countries deploy density differently based on geography, culture, and economic systems. Compare Japan (AHP 36 meters) with Australia (AHP 371 meters), which represent entirely different approaches to organizing human space. Corollaries – eetro regions, climatic zones, electoral college

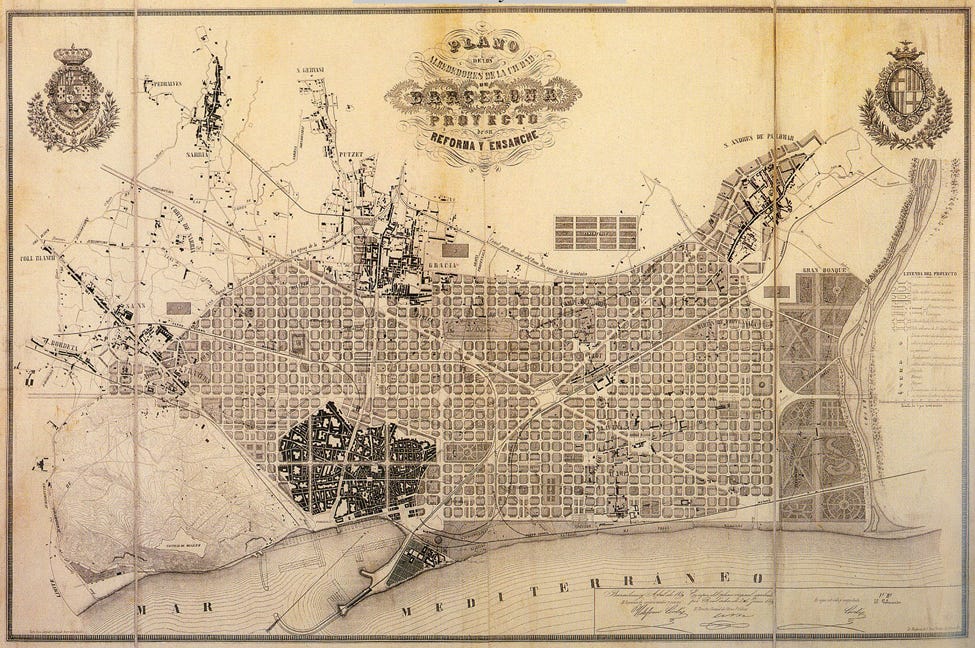

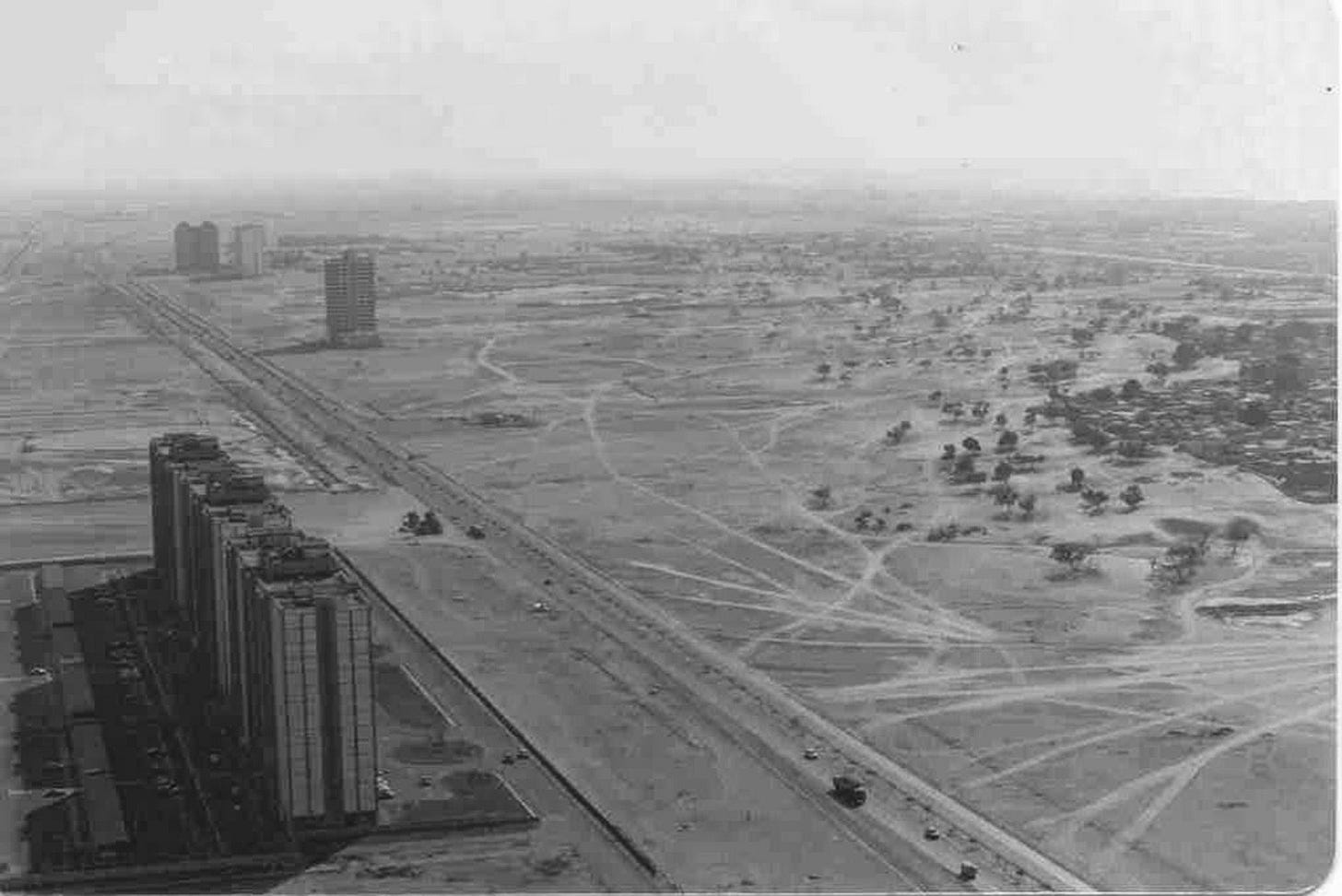

City (the image of density): Cities are where density becomes most tangible. Barcelona's sobre mesa-inducing fabric (AHP 20 meters) contrasts with Phoenix's sprawl (AHP 89 meters). Tokyo's AHP of 12.5 and Sydney's of 48 are well below their national averages. Unsurprisingly, people are closer together in cities. Corollaries – public transportation, infrastructure, sanitation

Neighborhood (community density) At this scale, debates emerge about "neighborhood character," parking, and building heights. It's where theoretical density meets lived experience. It is also the scale where irregularities in human proximity become the most contentious. The single-family homeowner protesting against the new multifamily development is also protesting against reducing the average physical distance between them and others in their community. Corollaries – FAR, zoning, design guidelines, setbacks, look and feel

Building (unit density): Housing markets and typologies lead to different proximities within buildings. Multifamily developments need to structure their unit mix along a range of parameters, including zoning, building code, financial structures, and market fit. Meanwhile, single-family residences market ample separation between the inhabitant and the next closest neighbor, with a picket fence for impact. Corollaries – typology, product type, layout efficiency, building code

Living Unit (personal density): The final scale is the individual dwelling, where density shapes our daily rhythms and personal space. Hong Kongers have only about 3.94 meters (12.7 feet) between them the next person in the same dwelling unit. An American household is much less crowded at an AHP of 8.24 meters (27 feet). Corollaries – Clutter, bunkbeds, garages, ADUs

At each scale, different concerns dominate. Global density can't be controlled directly, but all others can be shaped through policy, design, and culture. And since density is never distributed evenly, as we restrict area scale, we get more compressed.

Population Inflation

As planetary density increases, so does competition across multiple levels.

Cities battle for talent, investment, and cultural relevance.

Nations scramble for resources, influence, and economic advantage.

Individuals fight for housing, jobs, and even digital real estate.

Competition has grown keener than the 266% increase in world density since 1960. I want to call this phenomenon "population inflation" where the impact of each additional person on competition, resources, and opportunity outpaces their numerical addition to the population. Just as monetary inflation erodes purchasing power, population inflation diminishes the impact of each individual in markets, politics, and cultural spaces. Those who command the most attention have a global audience at their fingertips, but getting to the top is more difficult than ever.

We know that cities are as successful as the opportunities they create. As resources, opportunities, and attention become more contested, the intensity of competition has amplified beyond what raw population numbers would suggest, creating feedback loops that intensify pressure in desirable locations while leaving others behind. Access to cities is a scarce privelege in a denser, more competitive global society.

Recognizing population inflation and its impact on physical density is crucial if we hope to address today's challenges rather than yesterday's. Our policies and systems were designed for a world with different density pressures, and without acknowledging this inflationary effect, we'll continue applying outdated solutions to fundamentally transformed problems. Modern mobility has been made easier by shared borders, accessible air travel, and instant communication. Competition is no longer contained within national borders but radiates globally in real-time.

Engineering Around Density

As we grapple with this intensifying competition, we've developed technological solutions that attempt to mitigate or sometimes simply redistribute the pressures of density. Some create new challenges.

Remote Work: The pandemic forced a grand experiment in remote collaboration, with profoundly uneven outcomes. Cities that contained COVID-19 effectively (like in East Asia) maintained their physical work cultures. Western cities saw permanent shifts toward remote arrangements, essentially redistributing density from downtown cores to residential neighborhoods and exurbs. I've witnessed San Francisco's downtown transform from vibrant to vacant, not because buildings disappeared but because people did. Walking through the once-bustling Financial District now feels like touring an abandoned movie set—gleaming towers with empty lobbies, shuttered storefronts where lines once stretched around the block, and plazas designed for thousands now occupied by dozens. (This dramatic density collapse prompted me to run a studio at the Harvard Graduate School of Design focused on reimagining a future downtown San Francisco)

Digital Density: While physical density has tripled, digital density has exploded exponentially. Social media platforms concentrate billions of interactions in virtual spaces that didn't exist before. Algorithms determine which ideas gain visibility based on engagement density. Even as we physically spread out, we simultaneously crowd into digital environments that mimic and often intensify the competitive dynamics of dense physical spaces.

Globalized Production: We've engineered systems to move materials and products across vast distances, allowing manufacturing density to concentrate in specific regions while consumption spans the globe. This separation of production and consumption has profound implications for how we understand and manage density.

Density Changes Human Behavior

Every organism’s behavior is shaped by its environment.

Humans interact differently in groups versus individually. A revealing experiment by Ofer Feinerman, Tabea Dreyer, and their team at the Weizmann Institute of Science, compared how ants and humans navigate spatial challenges. When tasked with moving large objects through complex barriers, ant colonies consistently outperformed human groups. Their collective intelligence thrives in dense environments.

But when a single human faced off against a single ant on the same task, the human won handily. Our evolutionary success came from individual problem-solving, not collective coordination

Single Ant

Single Human

This paradox has huge implications for our dense world: unlike ants, who instinctively collaborate when packed together, humans tend toward individualism in crowded environments. The denser we get, the harder cooperation becomes. More considerations create more opportunities for discomfort. Ever tried to get a condo board to agree on a paying for a new roof? Now imagine scaling that to immigration policy.

I've come to recognize that I'm a bit of what you might call a "densoephile" and draw energy from the sights, sounds, and smells of human proximity. Subsequently, I've always found it easier to enter into dense situations than to withdraw from them. When I return to Hong Kong from San Francisco, or back when I was commuting to see my partner in New York while attending grad school in Cambridge, I feel energized rather than overwhelmed by the compression of humanity. But I've observed many colleagues and friends who experience the exact opposite reaction, retreating from density with the same enthusiasm I bring to embracing it (time to admit, I don’t understand camping). These personal density appetites shape not just our individual experiences but our collective ability to adapt to our increasingly compressed world.

Our species evolved to do things our own way, not to live harmoniously in tight quarters. Yet here we are—8 billion individuals sharing a planet that isn't growing in size, facing problems that require unprecedented cooperation.

The Generational Density Gap

This challenge is further complicated by the fact that those making decisions about our dense world formed their worldview in a much less crowded one.

A clear spatial consequence of our current gerontocracy is the political establishment has a bias toward sparsity. What’s the significance of 1960? This moment marked the convergence of post-war recovery, the acceleration of modern technology, and the birth year of many who now hold power and property. It's when our current economic and political systems were being solidified.

The average U.S. Senator is 65 years old, the average Fortune 500 CEO is 60 (Madison Trust: Fortune 500 CEO Ages), and the median world leader age is 62 (Pew Research: World Leader Ages). All were born around 1960 when Earth held just 3 billion people. Our decision-makers’ formative years occurred in a world less than half as dense as today's.

Nostalgia plays a powerful role in how we make decisions. Research shows that it functions as a cognitive shortcut, shaping present preferences through emotionally idealized memories of the past (Sedikides, Wildschut, & Baden, 2004). The global, national, and local densities that leaders instinctively reference often reflect the conditions of their upbrinings, not current realities. As cities evolve, these outdated mental models persist, anchoring decision-making in a density profile that is more memory than reality.

Is it any wonder that our policies seem disconnected from the pressures of today? In America, an increasingly older ruler class is governing a world that is denser and more complicated than ever before. From infrastructure investment to housing policy, transportation systems to urban planning, their mental models remain anchored in the spatial realities of previous generations. This entrenched spatial conservatism manifests as resistance to necessary adaptation, leaving us with cities designed for a population density that no longer exists.

This concept also passes the eye test. As we age, we naturally prefer less density: more space, fewer stairs, and more peace and quiet. This biological preference, combined with outdated mental models of "normal" density and the consolidation of resources and influence in older populations, creates a perfect storm of resistance to the very adaptations our cities need most.

We face a delicate challenge: honoring the wisdom that comes with age while acknowledging the limitations it can impose on future-oriented decision-making. When power is concentrated in the hands of those whose formative experiences were shaped by a fundamentally different density reality, it creates blind spots precisely where clarity is most needed.

Density Denialism

Despite this planetary compression, Western cities are increasingly resistant to adapting. The physical environment of the West has shifted from growth and dynamism to preservation and exclusion.

Restrictive Zoning: Compare Barcelona's urban fabric to most American cities. Barcelona's open grid embraces density while maintaining livability. Most American cities lock down development potential through complex zoning regulations that prevent adaptation.

The Exclusivity Mindset: There's an unspoken belief in many Western cities that they've "figured it out" and are already desirable, so why change? This morphs into a culture of exclusivity, where controlling who gets to live there becomes more important than growing the city itself. There's also a sense of "out of sight, out of mind." Westerners are largely unaware of the building advancements occurring around the world.

Building Culture in Decline: Our post-war construction is aging rapidly, yet we expect these deteriorating structures to appreciate in value. Other regions build quickly and create buildings of superior quality. In my experience as an architect, sometimes the only thing harder than building a new building in California or Massachussets is tearing down an old one, trapped in red tape and historic preservation battles.

Field vs. Pointal Verticality: Cities like Seoul, Shanghai, and São Paulo embrace "field verticality," where height is common rather than exceptional. Western cities often resort to "pointal verticality," isolated towers designed for iconicity rather than ecosystem development. As the urban scientist, Ramon Gras once commented to me, "the American model of urbanism is essentially to have a Manhattan at the center of a Phoenix."

Overall, the West has developed a bias for, depending how you look at it, inaction or for preservation of low density. While America's population hasn't grown at the same rate as the global population, it has still nearly doubled since 1960 (180 million vs 340 million). Meanwhile, the world is now 60% denser than when I was born and 300% denser than when my parents were born.

Fast vs. Slow Metabolisms

This resistance to density adaptation isn't uniform globally. Different urban centers respond to population pressure with dramatically different metabolic rates.

Rem Koolhaas, the Pritzker Prise winning architect (and my former boss) framed this contrast through the concept of the Developmental City, which he describes as urban environments where ambitious top-down planning leads to a metabolism of growth that outpaces traditional planning constraints in pursuit of rapid modernization economic development.

Not all cities approach density the same way:

Many Western cities are quickly resembling hardened fossils in that you can easily tell what they once were, but they lack the material to demonstrate what they are or will be. Meanwhile, developmental cities, from Lagos to Jakarta to Shenzhen, operate with an unstable equilibrium where construction, demolition, and reinvention are continuous. Their urban fabric is less a static monument than a living system.

Despite the dramatic increase in global density, the source of that densification is unevenly concentrated in the developing world.

The Growth Paradox

Our economic systems demand perpetual growth while operating on a planet with fixed resources and increasing density. More mouths to feed, more jobs to create, more shareholder value to increase, and all tying back to the density equation.

The consequences of this population increase crash against the reality of finite space. We've created economic systems that require endless expansion on a planet that doesn't grow.

Thinking in terms of density rather than just population forces us to confront these relationships. Density transforms population growth from a purely economic question into an eco-social one.

I don't think people really thought about density in the 1950s and 60s. They were too busy building modern society or trying to prevent us from destroying it. If the 20th century was about unconscious increases in population, the 21st century is about managing density. Even in regions with declining birth rates, density is still increasing locally as people move to cities and economic centers concentrate.

Heat

When Anders captured Earthrise in 1968, he showed us a world that seemed vast and full of possibility. If he took that same photo today, what would we see? Not just a more crowded planet, but a more connected one, a world where the distances between us have collapsed and our mutual dependencies have multiplied. We are more compressed.

This compression is making our planet hotter—and not just in the climatic sense. In a heat pump, when molecules are compressed, their density increases, pressure builds, and heat is generated. Our society works similarly. As we compress humanity into less relative space, we generate social heat through competition, friction, and intensified interaction. The higher the pressure, the more heat produced. We see this manifested as heightened competition for resources, housing, opportunities, and attention. If there is too much pressure, the system can collapse.

Yet this heat isn't entirely negative. Just as a heat pump harnesses compression energy for productive purposes, we need to channel our social density into constructive outcomes. Our economies require population to function, but they also need space for people to live, work, and thrive. Managing our density situation means, providing adequate housing, services, and infrastructure, expanding our capacity to accommodate the compression rather than fighting against it or allowing the pressure to build unchecked.

Peak Density

The world is expected to reach peak density in 2100 when the population hits 10.2 billion at an AHP of 120 meters.

This compressed future demands that we develop sharper spatial intelligence, or the ability to comprehend three-dimensional relationships and their human implications. As someone who trains young urban designers, I've witnessed how design education is having a harder time developing this critical skill, despite purporting to do so well. I’m concerned that instead of focusing on spatial intelligence, we've been distracted by peripheral goals, leaving us with a generation who lack the conceptual tools to navigate our increasingly dense reality.

Our future depends on leadership that understands density not as an abstract concept but as the fundamental organizing principle of 21st-century civilization. We need decision-makers who can see across scales, from global to personal, and dimensions, from social to physical, and craft policies and lead towards our denser reality.

What's particularly concerning is how younger generations, who have never known a less dense world, are navigating this reality. Many are retreating from physical gathering spaces into digital ones. This bifurcation between our physical and virtual existences may represent one of the most significant adaptations to our compressed planet, though not necessarily a healthy one.

The most profound challenges of our era, which include housing affordability, climate change, social polarization, and resource competition, all connect back to how we choose to live together in an increasingly crowded world. Earthrise showed us our planet as a shared home. Now, as that home accommodates more than twice the family it held then, we must reimagine how we organize our collective life within its unchanging continents.

Fundamentally, understanding density gives us not just a diagnostic tool but a prescriptive one. It reveals that our most significant challenges stem from our collective choices: how we work together, how we share space, and how we organize our communities. By embracing density as our core lens, we can transform our compressed planet from a source of conflict into a catalyst for innovation where cities, systems, and societies benefit from healthy human proximity.